RAVEL - “L’Enfant et les Sortileges”

GRAMMY® NOMINATED FOR BEST CLASSICAL ALBUM 2009

Nashville Symphony and Opera,

Chicago Symphony Chorus

Naxos

MENOTTI – “Amahl and the Night Visitors”

Nashville Symphony and Opera,

Nashville Symphony and Opera,

Chicago Symphony Chorus

Naxos

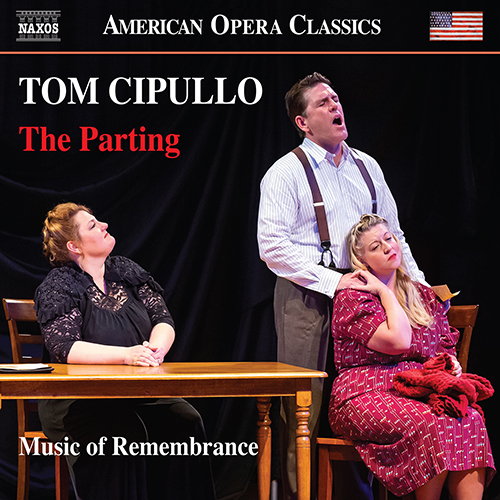

CIPULLO – “The Parting”

Tom Cipullo,

Tom Cipullo,

David Mason - Lyricist

Naxos

Reviews: RAVEL

American Record Guide

July 2009 | Charles H Parsons

Willis guides his Nashville forces with a jazzy exuberance mixed with delicacy that is just right. The singers are all robust, with a kind of American ferocity that would frighten any child…Julie Boulianne is a most masculine sounding mezzo Child. Many compliments to her for her touchingly-beautiful aria ‘Toi, le coeur de la rose’. The lovely dark-voiced Princess of Agathe Martel complements Boulianne quite well. Cassandre Prevost is winningly bright as The Fire and The Nightingale. The incisive Little Old Man of Philippe Castagner has a lot of French flair but sounds recorded in an acoustic too distant and different from the other singers. Castagner’s Frog is brilliant in voice and closer recorded. The Cats of Kirsten Gunlogson and Ian Greenlaw are an odd pairing, she a delightful, teasing feline, he too human sounding. Greenlaw’s Clock needs a brighter “Ding!” Kevin Short is an impressive Tree. Genevieve Despres is warmly emotional as the wounded Squirrel. Of course, all of the singers except Boulianne sing multiple roles. Everything comes together for a radiant Finale.

In an 18-minute+ bonus, Boulianne is heard in a rich, voluptuous rendition of Ravel’s three-part song-cycle, Sheherazade.

David's Review Corner

March 2009 | David Denton

Having heard all of the currently available recordings of L’Enfant et les sortilèges, I can assure you that none will give greater pleasure than this from Nashville. Taking a look at the illustrious list of performers who have already committed it to disc, that might seem a big claim, but for me the disc’s main attraction is the feel of a team rather than just a gathering of famous soloists. From the names I presume the cast gathered in Nashville are mainly French-Canadians and they instinctively shape the nuances of words, with the final ingredient coming from an orchestra that sounds more French than today’s top French ensembles. In the role of the naughty child, Julie Boulianne aims her voice between that of a child and Ravel’s more demanding vocal requirements without any seams showing. Maybe I should not pick out any one further singer, for in truth there is not a weak link anywhere, but for me Philippe Castagner’s Arithmetic Man is an absolute jewel. Even more important is that they sing their improbable rôles without those silly caricatures I have heard elsewhere. The conductor, Alastair Willis, admirably paces the score, pushing forward with real urgency when appropriate and whipping up some admirable climatic moments. The disc is completed with Boulianne singing Shéhérazade, and if she does not possess that langourous and ravishing quality of Regine Crespin in her legendary recording, she does create a feeling of sadness in the unrequited love in a very ordinary girl, which I find distinctly moving. I would want others, but it’s a view I could not be without. Add to all of these plus points a sound engineering that carries impact and clarity and yields nothing to any other recording, and you have my firm recommendation.

Audiophile Audition

August 2009 | Mike Birman

Ravel only composed two short operas during his career of which L’Enfant et les Sortileges (The Child and the Spells) was the second. Completed in 1925, it is based on the text for a ballet scenario by the French writer Colette. Ravel is famous for his brilliant use of orchestration and this work is no exception. It has a large orchestra with many unusual instruments. Some of the strangest instruments include a wind machine, a whip, a ratchet and a cheese grater. This seems appropriate for a work of fantasy in which everyday objects like a chair, teapot and grandfather clock come to life and sing. Some productions of this work that I’ve seen include more ballet elements, reflecting the origin of this work’s libretto by Colette…It is beautifully sung and played by the soloists and the Nashville Symphony Orchestra under Alastair Willis, however. The CD also includes Ravel’s 1903 three song cycle Sheherazade…These two works are often combined because they are both fantasies. Ravel depicts The Arabian Nights in his music which is often dreamy and mysterious. It is sung with the proper feeling of reverie by mezzo-soprano Julie Boulianne, and is one of the best performed versions of the piece that I’ve heard.

The sound on this CD is clear and just a little distant. That may be a deliberate attempt by the Naxos engineers to match the sound with the material. It is an effective combination as we are constantly reminded of the nature of the music.

Opera Canada

October 2009 | Neil Crory

Timing, as they say, is everything. How unfortunate then that this fine Naxos recording of Maurice Ravel’s 1925 “lyric fantasy” should be released at the same time as EMI’s star-studded recording with Sir Simon Rattle…but this Naxos budget recording featuring the Nashville Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Alastair Willis should not be ignored. Willis’s soloists are largely Francophone, and while they may not be household names, they rise to their tasks naturally, singing with Gallic charm and flair. Just listen to Canadian mezzo Julie Boulianne’s gorgeous “Toi, le Cœur de la Rose.” Besides Boulianne in the pivotal role as the Child, the cast includes several other outstanding young Canadian artists, notably mezzo Geneviève Després in her multiple roles as Mother, Dragonfly and Squirrel; soprano Cassandra Prévost as Fire and the Nightingale; and soprano Agathe Martel as the Princess and the Bat. Canadian-American tenor Philippe Castagner also enlivens the action with his characterful, animated portrayals of the Little Old Man and the Tree Frog…As a bonus, Naxos offers a compelling version of Ravel’sShéhérazade, also with Boulianne as soloist.

Reviews: MENOTTI

Fanfare

May 2009 | Henry Fogel

Alastair Willis shapes the music lovingly and with energy, and the Nashville Symphony plays with both skill and involvement. This recording is also the first to give the buyer a bonus—a 12-minute choral work dating from 1987 called My Christmas that represents Menotti at his most touching and eloquent…If you want a modern-sounding Amahl, this is clearly preferable to the only other stereo recording, particularly because of the livelier and more colorful conducting, and because of the choral bonus.

Opera News

April 2009 | Drew Minter

For more than fifty years, Gian Carlo Menotti’s yuletide gem, Amahl and the Night Visitors, has endured, evolving into a regular holiday offering…Amahl plays to our Christmas generosity of spirit, telling the story of a poor boy giving up his only possession, his crutch, to a newborn king. There is a charming naturalness to the interactions of Amahl with the three kings, who relate the new king’s birth and destiny. And Menotti provides many lovely musical moments—appealing woodwind interludes, two attractive choruses, an episodic shepherds’ dance.

The vocal music sounds most affecting when it is most declaimed. As Amahl’s mother, Kirsten Gunlogson brings rich mezzo tone to the role and terrific diction in the recitative portions. Menotti’s heavy orchestration makes her aria, “All that gold,” a bit heavy-handed and hard to comprehend. Boy soprano Ike Hawkersmith handles Amahl’s speech-song well and makes good use of his chest voice without going overly nasal. Character tenor Dean Anthony has the most dramatic flair as King Kaspar, while Todd Thomas and Kevin Short contribute gravity with their sonorous baritones. Menotti’s excellent sense of craft comes through in the quartet of the Mother and Kings, tautly composed polyphony, if a little uninspired melodically. Above all, Menotti’s dramatic sense of orchestration is clear and to the point, and the Nashville Symphony under Alastair Willis brings out all of its colors with direct sense.

Menotti’s anthem My Christmas also receives an attractive performance on this disc. Chorus master George Mabry gets a pleasant head-voice mix from the men’s sections of the Nashville Symphony choristers.

MusicWeb International

January 2009 | Simon Thompson

Menotti’s seasonal opera gets a welcome outing on Naxos with an all-American cast who give superb commitment to the score. The end product is very satisfying and a welcome addition to the work’s discography.

Italian-born Menotti spent most of his career in the United States and he is most renowned for his operatic work. Amahl is the most famous, but he also wrote popular works like The Saint of Bleecker Street together with vehicles for Beverly Sills and Placido Domingo, testifying to how highly regarded he was by singers. Amahl is his most popular work and has enjoyed the most exposure, written as it was for television. According to the helpful booklet note for this release it was shown on NBC every year between 1951 and 1966, together with several later productions and some runs on the BBC. It’s not difficult to explain its popularity: the small cast, unassuming stage requirements and seasonal appeal make it practical, while its music is remarkably lyrical for a post-war opera, and has all the attractiveness of a festive treat.

The story is straightforward: Amahl is a crippled boy who has problems with telling the truth. He lives in poverty with his mother near Bethlehem. One night they are visited by the three kings on their way to see the Christ-child. Amahl’s mother is tempted to steal some of their gold to help provide for the family, but when she is caught the kings forgive her because the child they are going to see has no need of earthly treasures. Amahl gives his crutch to the kings as a gift for the child and he is miraculously healed in consequence. During the final moments he leaves with the kings to go and worship the child.

Menotti’s achievement is to tell the story without lapsing into sentiment. He unstintingly portrays the desperate poverty of their circumstances, while contrasting this with the child-like optimism of Amahl himself. The atmosphere of a hot middle-eastern night is conveyed effectively too through, for example, Amahl’s shepherd pipes which open the piece and which are heard at various points throughout. The rustic dance which the shepherds put on to entertain the kings paints a good scene, as does the oriental march which accompanies the kings’ first appearance. He also uses operatic conventions convincingly: Amahl has to re-visit the door various times to convince his mother that the kings are outside. The repetitions this involved reinforce the musical and dramatic themes of the moment. If the miracle scene at the end feels a bit peremptory then it rises to a convincing climax and prepares for a warmly satisfying conclusion.

The all-American cast are clearly fully convinced by this work and they give their all in performance. No libretto is provided in the booklet, but the diction is so good that you won’t need it. As Amahl, Ike Hawkersmith is a strong vocal presence and his characterisation changes convincingly from a somewhat irritating brat to a believer stirred by his experiences. His aria about the family’s poverty (track 10) is very poignant, as is the scene where his mother later likens him to the Christ child (track 14). Kirsten Gunlogson is suitably waspish as Mother, while she too is transformed into a convincing penitent after the theft scene. The kings are all taken well, especially Kevin Short who brings an authoritative grandeur to his role as “the black King” (Amahl’s words). The contributions of the chorus are expertly judged: the Shepherds’ roundel is very attractive because no-one takes themselves too seriously and everyone is convinced to act their part. The orchestra pares down its textures very fittingly, held together capably by Alastair Wills, and the sound is immediate and close without being intrusive.

My Christmas is a rather sentimental setting for chorus of some of Menotti’s own words. There isn’t much to it, but its textures are appealing: the chorus are accompanied by flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, harp and double bass, with a touching restraint at its climax.

Naxos have done well to bring such a strong performance to the catalogue at budget price. It all adds up to a fine seasonal treat to be enjoyed with a cup of mulled wine and a mince pie.

MusicWeb International

February 2010 | Dan Morgan

Christmas Eve 1951, and the world’s first television opera, Amahl and the Night Visitors, is aired in the US. NBC, who commissioned the work, turned it into a festive tradition, screening it every Christmas until 1966. Here in the UK the BBC broadcast a live version in December 1955 and a filmed one in 1959. A third production, directed by Francesca Zambello and conducted by the late Richard Hickox, was aired in 2002. The latter would be most welcome on DVD or Blu-ray, as Hickox never got round to recording Amahl as part of his Menotti cycle for Chandos. For now this all-American version from Naxos has no rivals, with the exception of the original cast recording—in mono—conducted by Thomas Schippers (RCA Gold Seal 6485).

Menotti’s opera has the usual iconography of Christmas—the star ‘as large as a window and with a glorious tail’, the three Kings bearing gifts and the shepherds—with the crippled boy Amahl recalling Tiny Tim in Dickens’ Christmas Carol. The opera’s narrative, direct and unencumbered, is conveyed in music of great charm and simplicity; just listen to Amahl’s artless pipe-playing at the outset and his wide-eyed wonderment at the strange star in the night sky. Contrast that with the declamatory—and dissonant—piano chords associated with his exasperated mother. It’s a reassuring and familiar scene that also speaks of another—more innocent—age.

The boy treble Ike Hawkersmith is a convincing Amahl, combining good diction with a strong sense of character. Kirsten Gunlogson also makes a good impression as his mother, her voice big but not overwhelmingly so, her delivery clear and even. The recorded sound is very immediate—for that read closely miked—and some listeners may feel it’s a touch too bright. On the plus side this performance never slides into sentimentality, even when Amahl comforts his distraught mother in ‘Don’t cry, Mother dear’ (tr. 5). Their voices blend reasonably well in the touching ‘good nights’ that follow, the orchestra modulating into a stately, rather exotic, processional that heralds the arrival of the three Kings (tr.6).

Kevin Short has a big, imperious voice that suits the role of Balthazar, rather dwarfing his companions when they sing of their arduous journey. There is more than a hint of the swaying ox-cart of Mussorgsky’s Bydlo in the orchestral accompaniment at this point, a vivid evocation of their long and burdensome trek. The Nashville band’s playing under Alastair Willis is alert and upfront throughout; sample those scurrying pizzicato strings as Amahl tells his mother who is at the door, the Kings’ voices blending in sonorous unison (tr. 8). Their singing surely suggests a distant, churchly chant entirely appropriate to these holy men.

Indeed, Menotti’s score brings together so many different strands and styles in a most original and refreshing way. There’s a perky little march as the visitors enter the hut and simple piano flourishes accompany them as they warm themselves by the fire (tr. 9). The excitable Kaspar—who also happens to be deaf—is well sung by Dean Anthony. Ditto Kevin Short as Balthazar, who responds to Amahl’s cross-questioning with a mixture of patience and weariness (tr. 10). The interaction between Kaspar’s parrot and Amahl injects a note of humour, with King Melchior (Todd Thomas) cranking it up a notch or three as he explains that the mystery box contains all his worldly goods—and his treasured supply of liquorice (tr.11).

The close recording is not a major problem here, although the plucked basses that accompany Amahl’s mother, Melchior and Balthazar in tr. 14 sound jumbo-sized and rather muffled. That said, this trio certainly rises to a powerful climax, from which shepherds—laden with food—take their cue. There’s some lusty a cappella singing here, but the combined Nashville and Chicago choruses are much too close for comfort. However, the sinuous orchestral dance that follows—Boléro, anyone?—is beautifully done, with some delectable playing from the Nashville woodwinds (tr. 18). Balthazar’s thanks and the shepherds’ lyrical farewell are amongst the lovely moments when lingering doubts about this performance are dispelled and all caveats are forgotten. Quite magical.

The mother’s turmoil in tr. 20, as she ponders the Kings’ gold and what it could mean for her and Amahl, is sung with a Janácek-like intensity that reminds me so much of the late—and much lamented—Elisabeth Söderström in Sir Charles Mackerras’s Decca recording of Jenufa. But then Amahl is such an eclectic work, and I daresay most listeners will hear other echoes too. For once the immediacy of this recording pays dividends, adding real frisson to the mother’s anguish and the orchestral set-to that follows when she is caught trying to steal the visitors’ gold (tr. 21). Hawkersmith is most affecting as he vigorously—and physically—defends his mother, his repeated cries of ‘Don’t you dare’ (tr.22) a telling vocal counterpoint to his struggle with the Page.

One of the opera’s most potent messages—that of forgiveness—is brought home by Melchior, who tells Amahl’s mother that she can keep the gold (tr. 23). It is an aria of tenderness and compassion, radiantly scored. The other must surely be selflessness through the act of giving, as epitomised by Amahl’s spontaneous offer of his crutch as a gift to the Christ child. In doing so he finds that he can walk, a moment greeted first with awe and astonishment by the Kings and then with jubilation (tr. 24). The opera moves to a close as Amahl persuades his mother to let him accompany the three Kings to Bethlehem. Gunlogson sings with warmth and affection here, the parting duet accompanied by some of the loveliest music on this disc (tr. 26). The choruses return as the procession—Amahl in tow—resumes its momentous journey.

The Nashville chorus is centre-stage in My Christmas, which Menotti sets to his own texts in 1987. They sound remarkably bold and full-bodied here, their singing interspersed with music of chamber-like proportions. There is much to enjoy here, not least the ecstatic climaxes and Menotti’s unusual orchestration. Listen to the sudden instrumental fragments that recall Britten, and to the rhythms that hint at the Bernstein of Chichester Psalms. That said, the piece has a strong identity of its own, and I can’t imagine why we don’t hear it more. Oh, and a bottle of celebratory brandy for the Nashville horn player who rounds off the work so eloquently.

This Amahl is a real cracker, deserving of its place at the top of the tree.

Financial Times

March 21, 2009 Classical - Andrew Clark | Read Review

L'Enfant et les sortileges, Simon Rattle, EMI; Alastair Willis, Naxos

Ravel's fairy-tale opera, about a naughty child who receives a comeuppance in the animated world of cat, clock and china cup, is hard to pull off on stage but a joy on CD. Both these recordings are hugely sympathique , despite a failure of casting in the title role: neither mezzo - Magdalena Kozená for Rattle, Julie Boulianne for Willis - sounds remotely like a child (for that you need to go to the classic Maazel recording on DG). Rattle's cast is otherwise Francophone and charismatic, and he clearly loves this score as much as I: the Berlin Philharmonic plays with bewitching flair. Voices and execution in Willis's Nashville Symphony reading are not quite as high-octane, but it's still a disarmingly fresh and idiomatic performance. Apart from the disparity in price (Naxos much cheaper), a lot will depend on your preferred coupling: a radiant Boulianne in Shéhérazade or an enchanting Mother Goose from the Berliners.

The Guardian

March 20, 2009 Classical - Andrew Clements | Read Review

No composer has evoked the world of childhood more magically than Ravel, and the two works in which he did so most potently – the ballet Ma Mere l’Oye and the one-act opera L’Enfant et les Sortileges, with it’s deft, tender text by Colette – make an obvious pairing. Bothe pieces bring out the best of Simon Rattle, too, and throughout this disc, recorded in Berlin last autumn, his graceful grading of the orchestral textures and perfectly paced unfolding of its melodies is a pleasure in itself.

But despite Rattle’s beautifully realized evocations, and the Berlin Philharmoniker’s exquisitely coloured scene painting, the performance of L’Enfant never quite takes off.

Magdalena Kozena’s Child is more grande dame than naughty youngster, while the rest of the cast, including Annick Massis, Nathalie Stutzmann, Jose Van Damm and Francois Le Roux, never really get into their collections of cameos either. It’s all a bit too genteel, too refined in the wrong sense of the word. And though the playing of the Nashville Symphony on the Naxos disc can’t begin to compete with the Berlin sound, there’s something about the spirit of that performance under Alastair Willis, with Julie Boulianne as the Child, that seems closer to what Ravel might have had in mind. The performance of Ma Mere l’Oye may be worth the price of the EMI disc alone, but the delicate flavour of the opera comes across far more effectively in the Naxos account.

Yorkshire Post

March 13, 2009

Ravel L'Enfant et les sortileges/Sheherazade Naxos 8.660215 £5.99 | Read Review

The top disc recommendation for Ravel's L'enfante et les sortileges from Nashville, Tennessee? Unlikely, but true. Using French-Canadian soloists and a local Symphony Orchestra that outclasses even the best the French can offer, the whole performance, directed by Alastair Willis, is pure delight, and the sound quality is outstanding.

www.allmusic.com

Stephen Eddins

Maurice Ravel: L'Enfant et les sortilèges; Shéhérazade | Read Review

Given the number of very fine recordings of Ravel's L'Enfant et les Sortilèges, it's perhaps surprising that one of the very finest, most stylish, and idiomatic performances should have its roots firmly planted in the American heartland. Alastair Willis, leading the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, members of the Nashville Symphony Chorus, members of the Chicago Symphony Chorus, and the Chattanooga Boys Choir, conjures up a truly magical version of the opera. This is the result of a happy confluence of all the necessary elements: exceptional soloists who may not yet be international superstars, but who sing beautifully and are fully invested in bringing their roles to life; a thoroughly responsive chorus, exquisite orchestral playing, extraordinarily fine, nuanced engineering; and above all, Willis' loving attention the details of the score and his ability to bring an exhilarating musical and dramatic coherence to an opera that in lesser hands can seem quaintly episodic. This is a version of the opera that is brightly colored, whose incidents are dramatically charged and larger-than-life, just as they would be experienced from the perspective of The Child. Willis fully exposes the gift for humor that Ravel demonstrates in his brilliant and occasionally wacky orchestration and choral and solo writing. About half of the young singers who, judging from their bios, seem poised on the cusp of significant careers, are French Canadian, which probably accounts for the idiomatic authenticity of the performance, which easily outstrips that of some far more famous international casts. The choruses bring just the right loopy abandon to their depiction of the various groups of animals without ever stepping over the line into caricature, and their final madrigal is absolutely ravishing. The disc is filled out with an equally vivid performance of Schéhérazade, featuring a radiant, shimmering performance by mezzo-soprano Julie Boulianne, who also plays The Child in the opera.

The sound is fabulous. Apart from a brief balance problem in the first few measures of the opera, where the string bass' harmonics under the oboe duet sound tentative and are barely audible, details of orchestration pop out with sometimes startling, but entirely appropriate vividness. Highly recommended.

Der Schallplattenmann

March 30, 2009

Maurice Ravel / Nashville Symphony Orchestra & Chorus, Alastair Willis "L'Enfant et le Sortilèges · Shéhérazade" | Read Review

Klassik – Ravels kecke Oper in Nachwuchs-Besetzung(CD; Naxos)

Der Vergleich mit der fast gleichzeitig erschienen 'Star-Einspielung' der Berliner Philharmoniker unter Simon Rattle scheint ungehörig, wenn sich Nashville Symphony Orchestra & Chorus unter Alastair Willis und eine Riege junge Sänger daran messen müssen. Doch die Budget-Einspielung der Oper "L'Enfant et le Sortilèges" von Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) schneidet in diesem Vergleich alles andere als schlecht ab. Sicher, den Nashvillern fehlt noch ein gutes Stück zur Strahlkraft der großen Berliner Philharmoniker, aber sowohl das Orchester als auch das junge Sänger-Ensemble (Julia Boulianne, Geneviève Després, Philippe Castagner, Ian Greenlaw usw.) machen das durch Engagement und Spiel- bzw. Sangesfreude mehr als wett. Wenn man so will, 'spielen' die Sänger ihre Rollen hier überzeugender als die arrivierten der Hochpreis-Produktion. Unter der nicht zu beanstandenden Leitung von Alastair Willis kommt der ironisch-komische, kindliche, magische Charakter von "L'Enfant et le Sortilèges" besonders gut zur Geltung. Addiert man nun den deutlich geringeren Preis und den immer noch ordentlichen Sound zu dieser mehr als soliden Produktion, so sehe ich wirklich keinen Qualitätsunterschied zur 'großen' Aufnahme des Major-Labels. Wer auf große Namen verzichten kann, soll getrost zu dieser Ausgabe greifen.

Opernwelt

May 2009 - Jörg Königsdorf

Versunkene Paradiese, freche Pointenparade

Simon Rattle dirigiert Ravels «L’Enfant et les Sortilèges» mit einem Starensemble – und hat starke Konkurrenz

aus der amerikanischen Provinz | Read Review

Selten wurde so viel Aufhebens um ein unartiges Kind gemacht: Für ihre konzertante Aufführung von Ravels dreiviertelstündigem Meisterwerk «L’Enfant et les Sortilèges» versammelten die Berliner Philharmoniker im November 2008 eine Sängerriege, mit der man eine ganze Serie von Galaabenden hätte bestreiten können. Auf dem Podium scharten sich Stars wie José Van Dam, Annick Massis, Nathalie Stutzmann und natürlich Rattle-Gattin Magdalena Kozená – da durfte man durchaus auf eine neue Interpretation mit Referenzcharakter hoffen.

Dass der jetzt von der EMI veröffentlichte Mitschnitt zwar eine gute, aber keine außergewöhnliche Aufnahme ist, liegt jedoch gerade an den Stars, die zwar Stilbewusstsein, aber nicht in jedem Fall die optimalen Stimmen mitbringen. François Le Roux produziert als Großvateruhr viel heiße Luft, Annick Massis ist als Feuer etwas tantenhaft, und das komische Talent von Nathalie Stutzmanns China-Tasse hält sich in Grenzen (als Mutter ist sie allerdings besser). Der Star der Aufnahme ist ohnehin das Orchester: Die Berliner spielen Ravels Partitur ganz auf Raffinesse hin und entfalten, etwa in der Märchenbuch- Episode, die duftige Aura ihres lichten, schwerelosen Streicherklangs, betören mit einem Bläser-Sound, der selbst im Fortissimo noch makellos und rund ist. Selbst eindeutig komische Passagen wie das Katzenduett werden mit Delikatesse veredelt – ein verklärender Schimmer liegt über Rattles «Enfant» ebenso wie über der beigegebenen «Ma Mère l’Oye»-Suite, als seien diese Partituren Puppenstuben aus Gold und Silber, Paradiese einer versunkenen Kindheit.

Doch es geht auch anders: Das Nashville Symphony Orchestra besitzt nicht die Klangkultur der Berliner Philharmoniker und kann vom Dirigenten bis zu den Sängern nur No- Names aufbieten – und doch ist die jetzt bei Naxos vorgelegte Einspielung erheblich unterhaltsamer als das Berliner Hochglanzprodukt. Denn die Amerikaner spielen Ravel aus einer Perspektive, die tatsächlich als Alternative zu den klassischen französischen Aufnahmen von Ernest Bour, Ansermet und Maazel taugt: als herrlich freches Musikkabarett, als schräge Revue, bei der die Kunstform Oper kräftig durch den Kakao gezogen wird. Da wird gejammert, geächzt, gemaunzt und gequakt, dass sich die Balken biegen, und zugleich sorgen das direkte Klangbild und der trockene Ton, den Dirigent Alastair Willis anschlägt, dafür, dass die Pointen sitzen. Ein Ravel à la Bernstein, bei dem es auch gar nicht so wichtig ist, ob die Stimmen Top- Qualität haben. Die Klage des Eichhörnchens beispielsweise hat den schrägen Charme einer abgeranzten Chansonsängerin. Dass die als Füller beigegebene «Shéhérazade» nicht von diesen Qualitäten profitieren kann, lässt sich verschmerzen. Zu Julie Bouliannes abgesungener Märchenerzählerin gibt es im Katalog genug Alternativen. Für manche Stücke braucht es eben doch einen Star.